Focus: Carbon Credits - Enabling Market Mechanisms to Curb Emissions

Author: Luca Gentzbourger

What is a Carbon Credit?

A carbon credit is a general term referring to both carbon allowances and carbon offsets, also known as international credits, however their issuance and uses differ. Carbon allowances operate solely in the compliance market, issued and regulated by mandatory national, regional, or international carbon reduction regimes. These allowances are used by emitting companies to comply with regulations. For every ton of carbon emitted, a carbon allowance must be redeemed by the company. Interestingly, since the implementation of the secondary and futures markets, financial actors have been increasingly interested, which has led to strong liquidity growth. Allowances are essentially a market derived tax to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

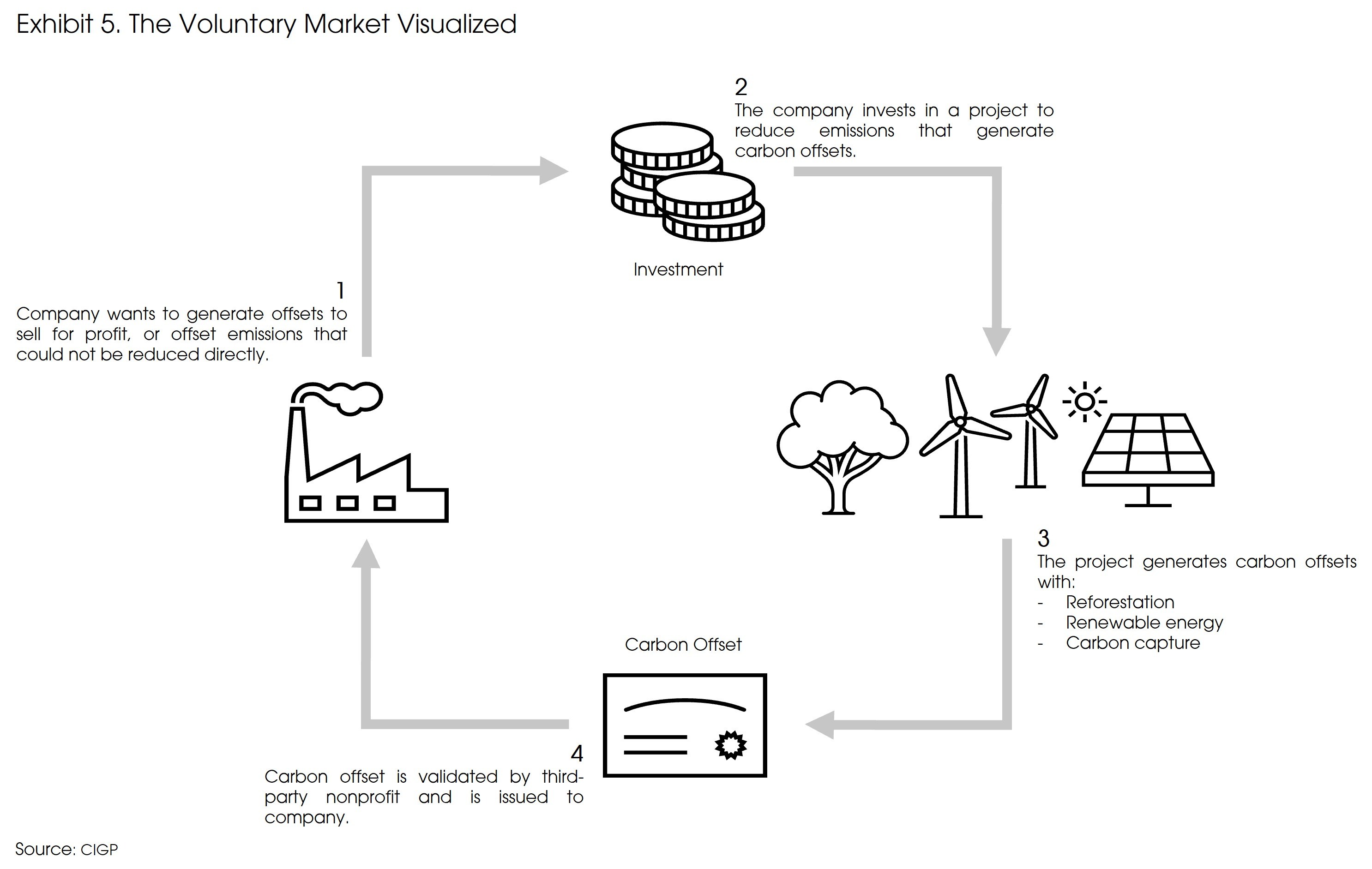

On the other hand, carbon offsets are mainly used in the voluntary market. Instead of being issued by regimes, they are created by companies actively removing carbon from the atmosphere and sold for profit. This market allows companies and individuals to purchase carbon offsets on a voluntary basis with little to no intended use for regulatory compliance purposes. Currently, the most common use of these certificates is an option offered by airlines at checkout to offset the emissions of one’s travels.

Both carbon allowances and offsets are tradeable certificates that provide their holders the right to emit one ton of carbon dioxide or the equivalent mass of another greenhouse gas (methane, nitrous oxide, or hydrofluorocarbons) equal to one ton of carbon dioxide. Once a certificate is used to offset emissions or comply with regulations, the respective certificate is invalidated, and can no longer be used or traded. To quantify one ton of carbon, we can look at the emissions impact of a flight from Chicago to Hong Kong in a Boeing 777, which emits 352 tons of carbon, 34km per ton of carbon. Alternatively, the average emissions per capita in industrialized countries is 9 carbon tons per year, while unsurprisingly the United States averages 16 according to the World Bank. To visualize, a ton of carbon fits in an 8x8x8 meter cube.

Carbon Allowances & The Compliance Market:

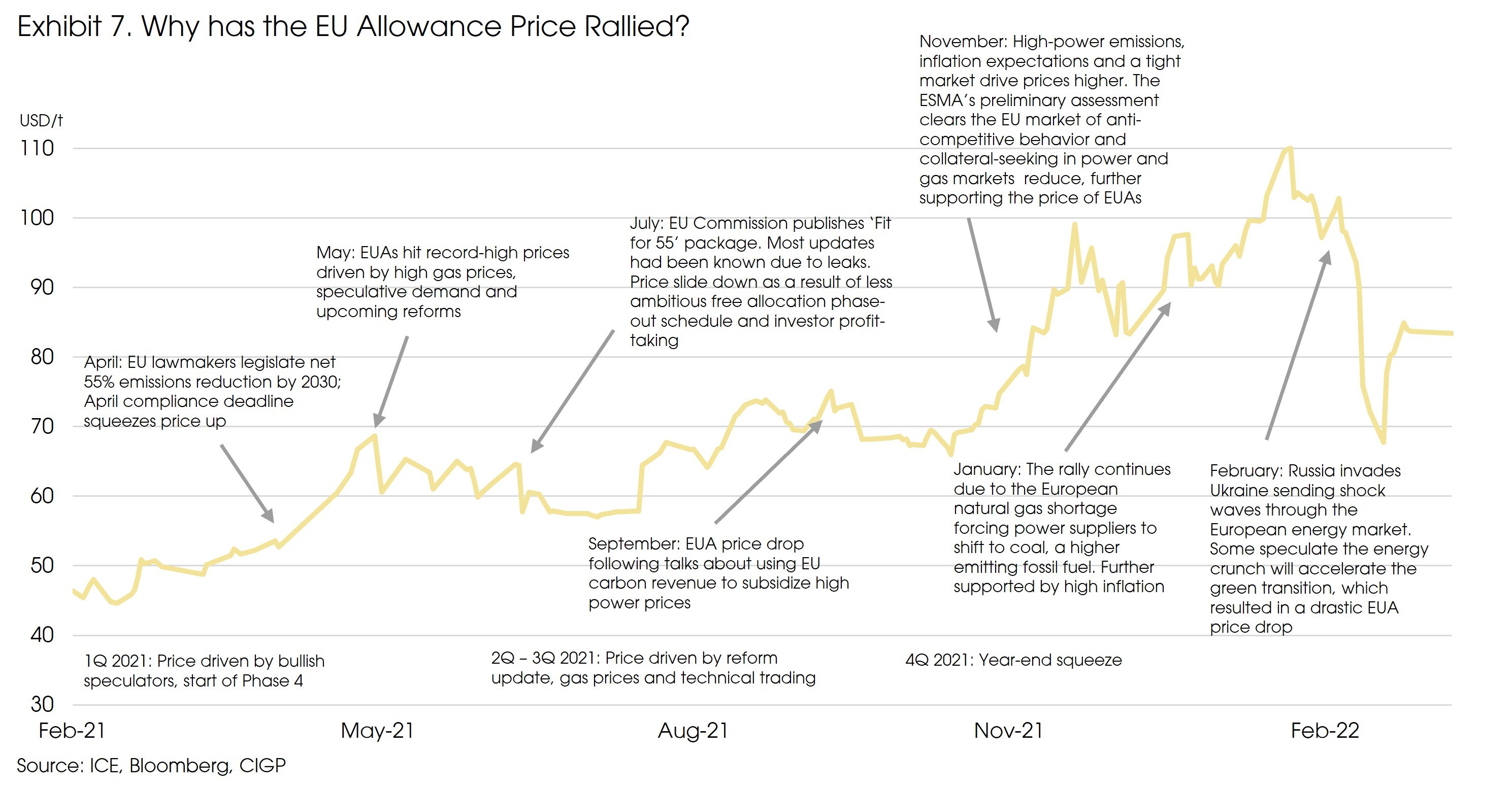

Carbon compliance markets are a regulated and mandatory national, regional, or international carbon reduction regimes that apply to certain high emitting sectors. The concept was introduced at the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and was adopted in 2005 when the first Emissions Trading System (ETS) was launched, the EU ETS. At the time the goal was to reduce global emissions by 5% based on the 1990 levels. A target which has been amended over the years. In 2021, the European Commission published the Green Deal, which aims to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Today, the global carbon compliance market is worth over USD 851 billion with 41 countries having implemented carbon pricing, representing 46 carbon markets, as some markets remain regional. It is important to note that allowances are not internationally fungible as prices vary by market. Price variation is due to the individual region’s environmental policy, economic shocks, their ETS’ scope of industries and its market capitalization.

The various international ETS’ are independent from each other and operate under their own unique parameters. In theory, each ETS will structure their system to best suit the regional needs for curbing emission, however unfortunately politics tend to also influence the selection of sectors required to comply. For example, the EU ETS and California Cap-and-Trade cover an estimated 55% and 80% of regional emission respectively, covering a wide range of high emitting sectors. However, the RGGI system, in the Northeastern United States, was met with significant political push back and therefore holds a smaller share of total emissions by only covering companies in the power generation sector that use coal, oil and natural gas to generate electricity.

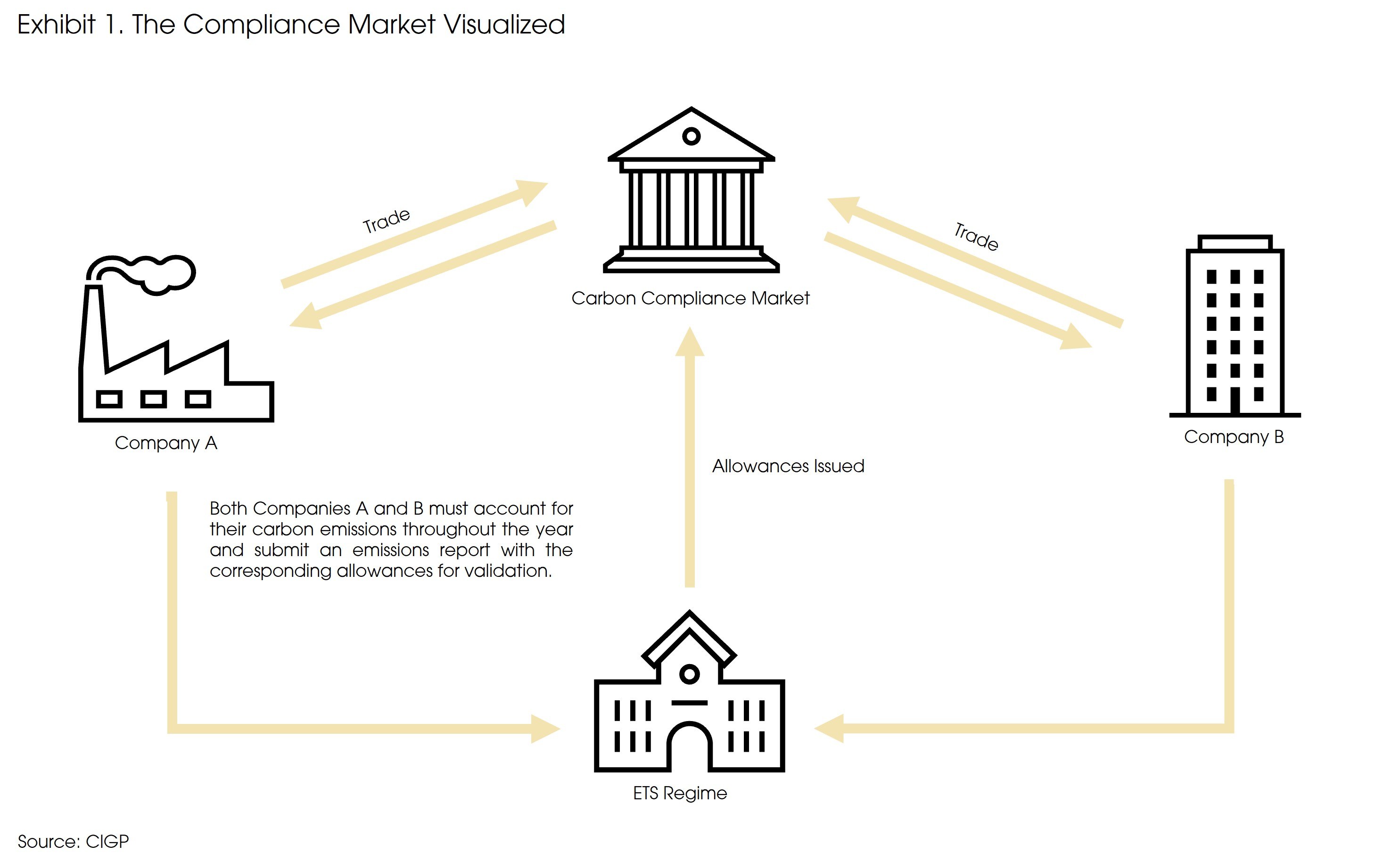

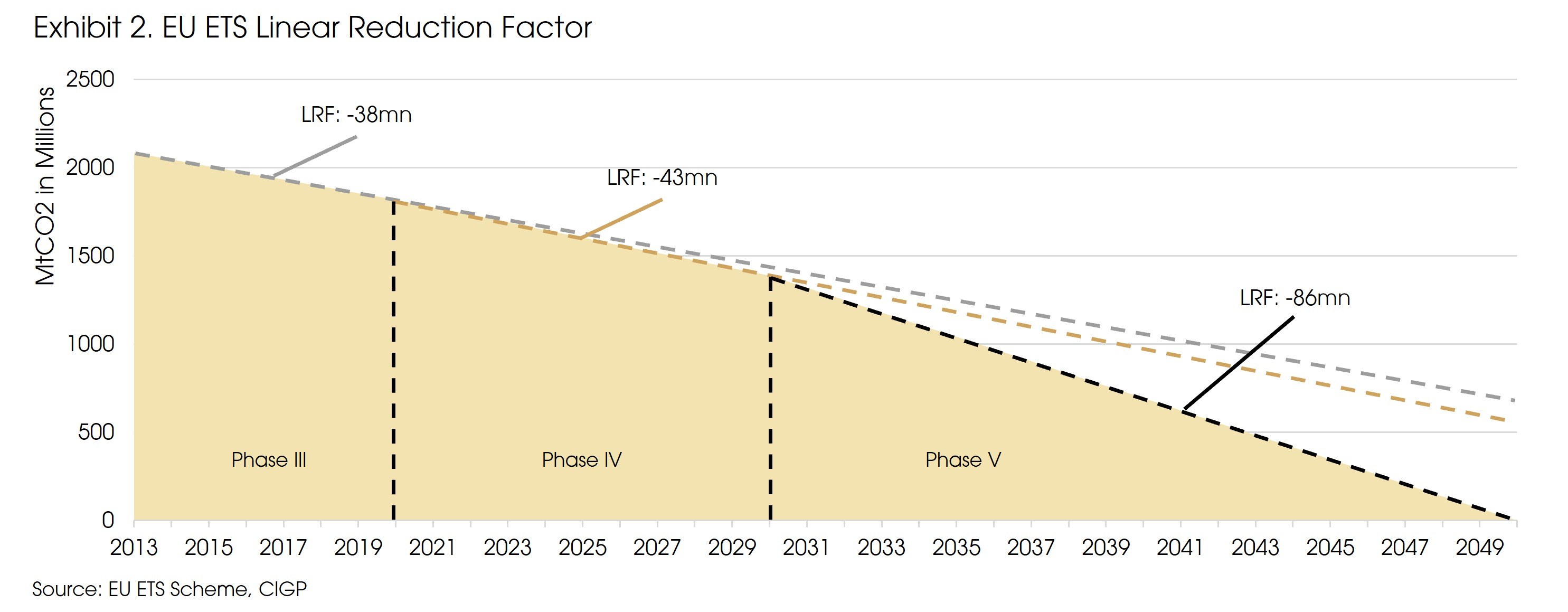

Despite their differences, all ETS’ operate under the Cap-and-Trade model in which the respective regime sets a cap on the total carbon allowances issued in a certain time period, typically 4-to-10-year, and then lets the secondary market trade freely to determine the market price of an allowance. The cap is determined by the emission reduction target, creating an accountable mechanism to curb emissions. To remain below the cap, a linear reduction factor is applied, reducing the yearly issuance of allowances. For example, during phase 3 of the EU ETS (2013-2020), the number of allowances issued decreased from 2.1 billion in 2013 to 1.8 billion in 2020, given the linear reduction factor of 38mn per year. The reduction factor has increased to 43mn for the 2021-2030 period and is set to double to 86mn afterwards. As the supply reduces over time, allowance prices should rise, further incentivizing companies to invest in clean technology as it becomes the cheaper alternative to purchasing the mandated allowances. Carbon markets are structurally designed to create a supply-demand imbalance, effectively an artificial market created to drive prices up and accelerate the green transition.

Tracking Emissions in the Compliance Markets:

Companies subject to mandatory participation in an ETS must fulfill certain obligations to register and comply with regulations. According to the Netherlands Emissions Authority, an application must be submitted to one’s respective emissions regime for a greenhouse gas emissions permit by building a monitoring plan that demonstrates accurate emissions measurement methods. Typically, emissions will be measured based on the facility’s production quantity, which are used to calculate the corresponding emissions. Once approved, an account must be opened with the emissions regime’s registry to hold and trade allowances. It is the responsibility of the emissions regime to conduct due diligence processes, validate company emission reports, and actively monitor compliance by conducting random inspections of the 12,000 companies covered by the EU ETS.

Impact Across Sectors:

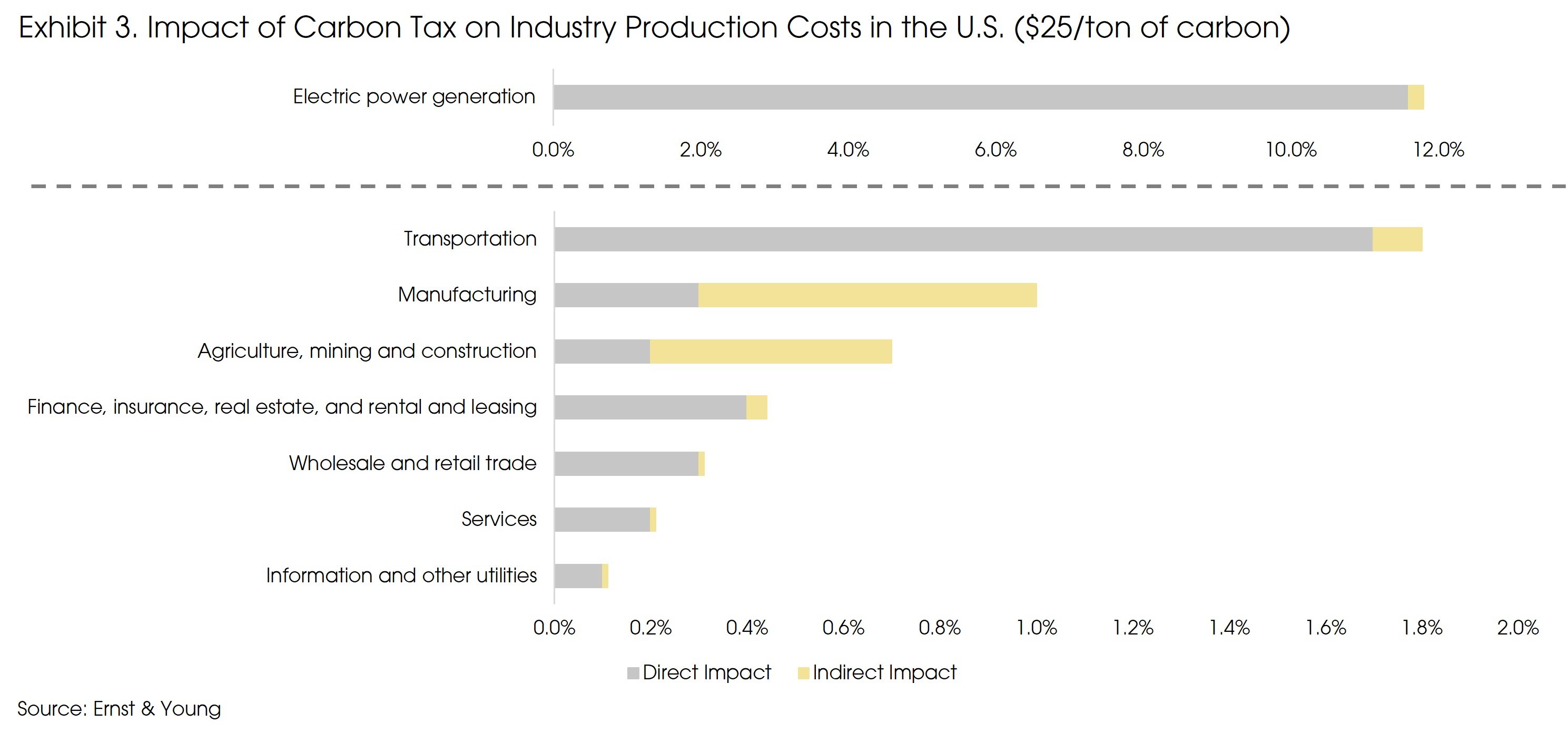

Overall, the implementation of a compliant carbon system will increase production costs across all industries, however, the impacts will vary significantly by sector and sub-sector. According to an Ernst & Young study, the implementation of a $25 carbon price in the United States would increase production costs by 0.7% on average. The power generation industry would be affected the most, with production costs rising by 11.8%. However, it is important to note the sectors most affected by the implementation of such a tax will force a rapid transition to net-zero. Their rapid transition may be a burden today but will prove to be an advantage down the line once they’ve already been established as net-zero businesses and other harder-to-transition sectors continue to struggle to reduce emissions.

The power generation sector is expected to be the most responsive sector to carbon price signals. Most models predict carbon prices will lead to a substantial reduction in CO2, as it is both cheaper and more straightforward to reduce emissions when compared with other sectors. The key reason is that carbon prices directly change the relative cost of different electricity generation technologies. The price of coal-fired generation, which produces a high amount of CO2, would rise substantially relative to the price of electrical generation fueled by natural gas, nuclear power, or renewables.

The transportation sector isn’t anticipated to immediately reduce emissions for two key reasons: 1) it is hard for consumers to significantly alter their driving habits based on fuel costs; 2) the sector doesn’t offer easy opportunities for fuel switching. Most of the population has already invested in a gas-powered vehicle, which cannot be converted, but needs to be replaced, leading to a high switching cost for individuals. Of course, as fuel prices rise through carbon pricing, consumers will be incentivized to purchase an electric vehicle, however, mass adoption is expected to be slow.

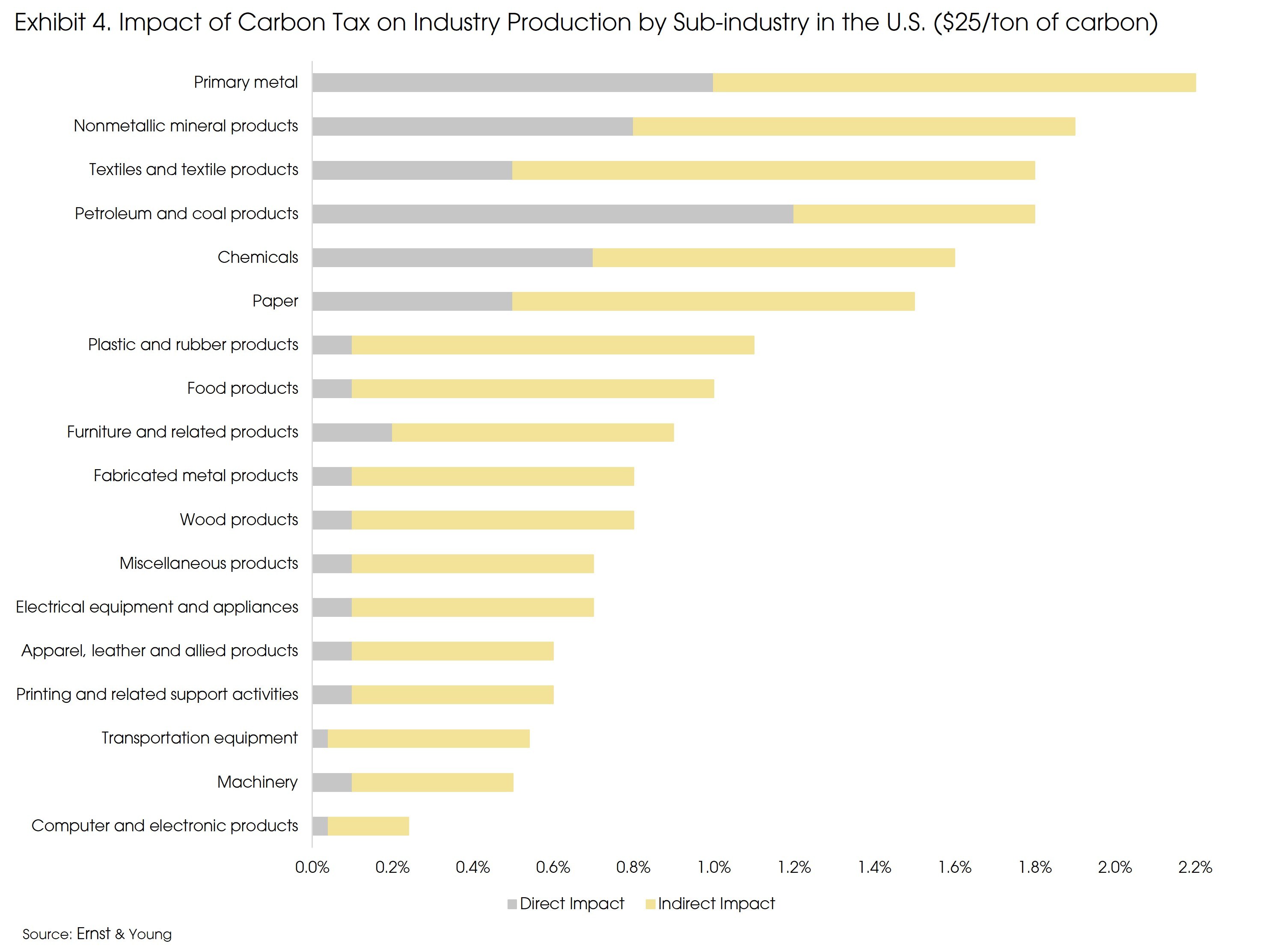

The high temperature manufacturing sector is another major source of emissions, coming from the productions of iron, steel, chemicals, plastics, cement, aluminum, pulp, paper and ceramics. Companies in these industries pay close attention to fuel input costs and therefore are likely to be responsive to changes in those costs under a carbon tax. However, finding a fossil fuel substitute is not easy. Both green hydrogen and ammonia are promising alternatives but remain in their early stages and are currently unable to meet the demand of manufacturers. Thus, certain sub-sectors will be more affected than others.

Carbon Offsets & The Voluntary Market:

Carbon offsets operate similarly to carbon allowances. However, as mentioned above, these offsets aren’t issued by governments but earned by companies actively sequestering carbon. The voluntary market is currently valued at USD 1 billion, a fraction of the compliance market.

Sequestering carbon can come in many forms. The most common ones are reforestation projects, biochar utilization, direct air capture and storage. Reforestation adds to the planet’s net carbon storage and helps moderate carbon emission in the atmosphere. Biochar, also known as biomass, is a charcoal-like substance that’s made by burning organic material from agricultural and forestry wastes and is used in composting and farming, while also sequestering carbon by locking it in the soil for thousands of years. Lastly, the direct air capture mechanism is essentially a large vacuum with heated filters that capture CO2 for storage.

Carbon offsets are cheaper than carbon allowances, as they carry inherent risk, and for the most part cannot be used to comply in a compliance market. If the carbon capture mechanism used to create the carbon offset fails, and releases carbon back into the atmosphere, the respective offsets must be invalidated. This and the whole voluntary market are currently overseen by non-profit independent registries, responsible for verification, authentication, and monitoring of carbon offsets. However, their efficacy is often called into question.

Although carbon offsets typically have no use in the compliance market, some markets, such as the California Cap-and-Trade, allow the use of both carbon allowances and offsets to comply with emissions. However offsets’ usage is limited to 4% of a company’s total emissions liability. The EU ETS also used to accept carbon offsets in a limited capacity but not anymore.

The theory in creating the voluntary market is to incentivize the sequestering of carbon by making it profitable. However, the current system has proven to be flawed and lacks the necessary regulatory oversight to ensure captured carbon remains contained, as none of the sequestering methods are perfect. International criticism has led the EU and other compliance markets to shift away from the concept or limit their uses significantly.

Carbon Allowances as an Uncorrelated Asset Class?

Carbon allowances trading in the compliance market have increasingly become attractive as an uncorrelated asset class, with the five most liquid markets generating positive returns since their inception, the EU ETS, California Cap-and-Trade, RGGI, UK ETS and New Zealand ETS. Additionally, each exhibits a unique return, volatility, and correlation profile, which can provide some diversification within the niche market. Typically, individual carbon markets are driven by their political environments, policy structure and local energy prices.

Carbon Investment Vehicles:

The purchase of physical allowances requires setting up an account with one of the emission trading system, which is not easily accessible by the average investor. Therefore, alternative investment vehicles are on the rise by utilizing the growing futures market. The first financial actors to enter the scene were hedge funds, seeking to capitalize on arbitrage opportunities in the market. One such fund that we have come across, actively manages their investments, and mainly invests in options and futures, with some physical allowances across the EU ETS, California Cap-and-Trade, RGGI, UK ETS and New Zealand ETS.

More recently, ETFs have entered the market and have overtaken hedge funds in assets under management. The ETFs employ a passive long only strategy, and only invest in futures. The largest ETF at the moment invests in the markets mentioned above except the New Zealand ETS.

The two investment vehicles mentioned above have been solely focused on the compliance market and fluctuate based on the price of carbon allowances. However, following the carbon conscious trend, a new niche sector is on the rise, carbon accounting. Today, these small privately owned software companies relieve conglomerates from the cumbersome task of accounting for carbon emissions in their extensive supply chains. The sector is currently in a tailwind after the SEC published a proposal to mandate all public companies to disclose their direct and in-direct emissions. Although the niche sector may become an essential tool for publicly listed companies, there is still no clear indication of their long-term viability.

Additionally, some believe in the future of the voluntary market, and seek to gain exposure in the market’s infancy. We have seen a publicly listed company that is actively investing in carbon sequestering initiatives to generate carbon offsets and sell them for profit. A potential tailwind for such a company and the voluntary market could be the implementation of stringent regulatory oversights to validate and monitor offset issuances, which may attract ETS’ to expand/permit the use of carbon offsets for regulatory compliance. Although the effectiveness of the Voluntary Market has yet to be proven, it’s a promising solution to reducing emissions and could play a significant role in curbing global emissions in the long-term. However, our focus remains on the established compliance market which dwarfs the voluntary market with valuations of USD 851 billion and USD 1 billion respectively.

All carbon investment vehicles still have short track records and demonstrate high sensitivity to environmental policy and regulations. Thus, changes can occur quickly and without warning depending on which side of the political spectrum the majority falls.

Source: Bloomberg, California ARB, EU ETS Scheme, European Commission, EY, ICE, NEA, World Bank, WSJ, CIGP